Who will decide the winner of the AI competition? Perhaps it is: gas turbines

Barclays pointed out that gas turbines are becoming the most critical constraint in AI power supply, with project cycles lasting four to five years from contract signing to full-load operation. Even after the delivery of large gas turbines, it often takes an additional 18 to 24 months of construction, debugging, and grid connection to truly establish stable and commercialized power generation capacity

While the market continues to focus on GPU computing power, advanced processes, and HBM supply rhythms, Wall Street's research perspective is quietly sinking, gradually shifting towards the more fundamental and constraining infrastructure aspects of the AI industry chain.

According to the Chasing Wind Trading Desk, in Barclays' latest thematic research report, a seemingly "anti-technology" yet highly decisive judgment has been repeatedly emphasized: The real bottleneck in the AI race is shifting from chips to electricity, and among all feasible solutions at this stage, gas turbines are becoming the most constraining key link.

This is not because gas turbines are particularly cutting-edge; on the contrary, it is precisely because they are mature enough but have become difficult to rapidly scale up.

What AI Truly Changes is the "Temporal Attribute" of Electricity

Compared to the traditional cloud computing era, the demand for electricity in AI data centers is undergoing structural changes. The issue is no longer simply "how much electricity is needed," but rather "can electricity be delivered at the right time and in a sufficiently stable manner?"

Barclays states that under large-scale training loads, delays in electricity access and uncertainties in grid connection will directly translate into idle computing power and decreased capital efficiency. In this context, "speed-to-power" is no longer just an engineering metric but is becoming a core variable that affects deployment pace and commercial returns in the AI race.

For this reason, although the public grid remains more attractive from a long-term cost perspective, reality is forcing more and more AI data centers to turn to "bring your own power (BYOP)" solutions. Under current technological conditions, gas turbines remain the only option that can achieve a realistic balance between scale, stability, and maturity.

However, the problem is that this choice itself points to a deeper constraint.

An Underestimated Fact by the Market: Gas Turbines Are Not Being Scaled Up for AI

On the surface, the rapid rise in demand for gas turbines seems highly correlated with the construction of AI data centers, but Barclays' research report repeatedly reminds us that simplistically interpreting this round of demand changes as "driven by AI" is itself a misreading.

In fact, AI is just one of the new demands. At the same time, the replacement of base load after the global coal power phase-out, the increased penetration of renewable energy leading to peak shaving demand, and the ongoing capital expenditures in the LNG and oil and gas supply chains are all simultaneously squeezing the same gas turbine supply system.

This means that AI projects do not enjoy "supply priority." Whether it is manufacturing capacity, engineering resources, or high-temperature materials and key components, AI must share the same supply chain with other long-term demands. In this context, OEMs have not, and are unlikely to, reconstruct a completely new production line specifically for AI data centers.

"Delivery" Does Not Equal "Power Generation," Time Delays Are Seriously Underestimated

One significant yet easily overlooked fact in the report is that: Even after the delivery of large gas turbines, it often still requires 18 to 24 months of construction, debugging, and grid connection cycles to truly form stable and commercializable power generation capabilities. This time lag is not a detail at the engineering level, but an important variable that can change macro judgments. Multiple cases show that the project cycle from contract signing to full-load operation often lasts four to five years.

This also means that even if an order is placed immediately, the AI computing power will likely not "consume" this additional electricity until the next capital cycle. The implicit judgment given by the research report is: The tight constraints on electricity faced by AI may not ease in the short term, but rather continue until around 2030.

The restraint of OEMs is itself a cyclical signal

On the supply side, there is a significant gap between the market's intuitive imagination of "capacity expansion" and the actual behavior of OEMs.

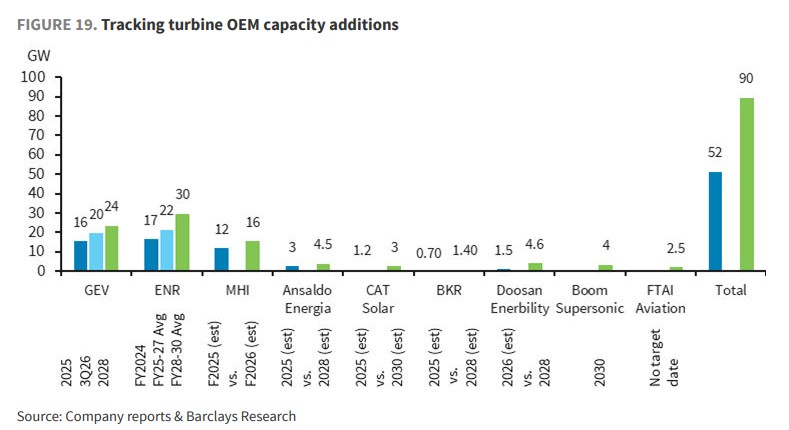

According to the situation analyzed by Barclays, whether it is Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, GE Vernova, or Siemens Energy, the current capacity expansion is more about process optimization, the resumption of old models, and overtime production, while the capacity that truly relies on new capital expenditures will mostly only gradually materialize after 2027-2028.

More importantly, OEMs have generally adopted a more cautious strategy combination—slowing down the pace of expansion, significantly increasing the proportion of capacity reservation deposits, and conducting stricter screening of projects. This approach is not due to insufficient demand, but rather the industry's heightened vigilance against the recurrence of overheating cycles. In this cycle, the supply side is not eager to break the tight balance.

The research report also presents a rather counterintuitive judgment: As the proportion of renewable energy continues to rise, the importance of gas turbines in the power system has not decreased, but has been further strengthened.

The rapid expansion of wind and solar power has increased the overall volatility of the grid, while the practical constraints of energy storage in terms of cost and duration make stable, dispatchable power sources still indispensable. In this structure, gas turbines are not a "transitional technology before being eliminated," but rather an intermediate link that cannot be skipped in the energy transition process.

Overall, what this Barclays report truly conveys is not a simple story of "AI driving traditional energy," but a deeper structural judgment: Under the overlay of multiple long-term demands, the gas turbine industry has lost the ability to rapidly expand supply.

AI did not create this problem; it was merely the first and earliest customer to thoroughly expose this bottleneck to the market. If the GPU determines the speed limit of a single computation, then what truly determines whether this AI competition can start on time and who is qualified to stay in the arena for the long term is the gas turbine