The "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma" and the Rise and Fall of the Global Dollar Cycle

This article explores the rise and fall of the global circulation of the US dollar since the 1980s and its impact on the global economy. As a major trade deficit country, the flow of the dollar has facilitated global imbalances. After the dollar decoupled from gold, the global economy entered the "Jamaica System," exacerbating the imbalance phenomenon. Currently, the strength of the dollar threatens the long-term hegemony of the United States, forming the "fundamental Triffin dilemma." The "reciprocal tariff" policy introduced by the United States in 2025 is seen as a measure to curb the large circulation of the dollar, marking the beginning of its decline. China should learn from this and promote the internationalization of the renminbi and the expansion of domestic demand

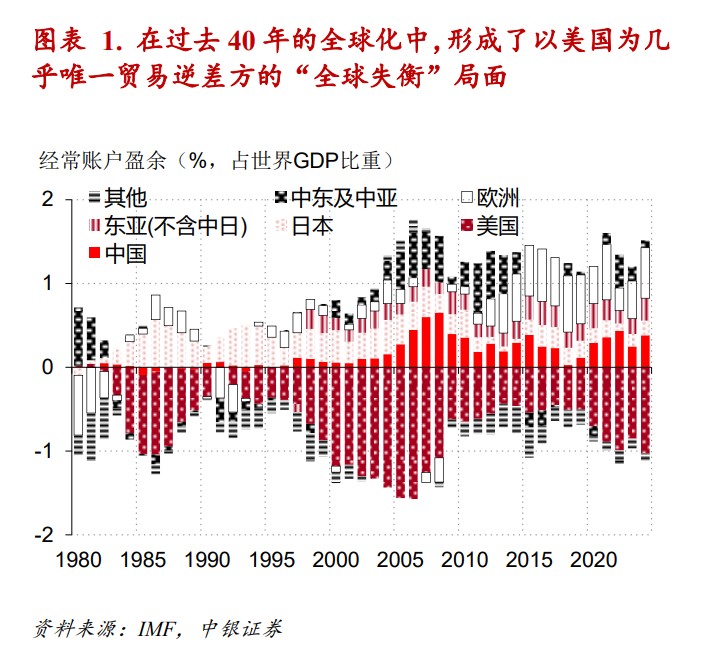

Since the 1980s, the process of globalization has led to the formation of "global imbalances" in the international economy. Among them, the United States is the primary trade deficit country, with most of the global total trade deficit originating from the U.S. In this global imbalance, alongside the global flow of goods, there is the global circulation of the U.S. dollar—dollars flow out of the U.S. through the purchase of goods from other countries and flow back into the U.S. through investments in the U.S. financial markets by other countries. It was the decoupling of the dollar from gold in 1971 that ushered the world economy into the "Jamaica system" era, freeing it from the automatic correction of trade imbalances imposed by the "Hume mechanism," making global imbalances possible. Therefore, it can be said that the global circulation of the dollar has given rise to global imbalances.

Within the flourishing picture of the global circulation of the dollar lies the seed of its decline. Currently, the demand for dollars from surplus countries remains strong, but the seeds of decline are sprouting in the U.S. The dollar has caused the U.S. to suffer from "Dutch disease," leading to a decline in manufacturing and hollowing out of industries, threatening America's long-term hegemony. The U.S. is facing the "fundamental Triffin dilemma," which is the contradiction between U.S. hegemony and dollar hegemony—U.S. hegemony has created dollar hegemony, but dollar hegemony, in turn, can lead to the decline of U.S. hegemony and ultimately the loss of dollar hegemony.

The "reciprocal tariffs" introduced by the U.S. in April 2025 can be seen as a policy measure to suppress the global circulation of the dollar, reflecting the U.S. government's choice to consolidate its hegemony at the cost of dollar hegemony when faced with the "fundamental Triffin dilemma." In this sense, "reciprocal tariffs" are a symbolic event marking the transition of the global circulation of the dollar from prosperity to decline. The subsequent weakening of the dollar and U.S. Treasury bonds, along with the strengthening of gold prices, are manifestations of the turning point in the global circulation of the dollar.

From the rise and fall of the global circulation of the dollar, our country can draw three insights. First, in the long term, the internationalization of the renminbi should not aim to replace the dollar or establish renminbi hegemony. Second, in the medium term, our country should actively expand domestic demand and promote consumption transformation to reduce reliance on "external circulation" through a smoother "internal circulation." Third, in the short term, our country is likely approaching the "ceiling" of external demand.

Global Imbalances and the Global Circulation of the Dollar

Since the 1980s, the process of globalization has led to the formation of "global imbalances." Global imbalances are characterized by a significant increase in the share of total trade surpluses of countries in the world relative to global GDP. Since the Earth is a closed economy, if we do not consider statistical errors, the sum of surpluses from all surplus countries should equal the sum of deficits from all deficit countries, presenting a mirror relationship between the two. Therefore, in global imbalances, the increase in trade surpluses is accompanied by an increase in trade deficits.

In the analysis of trade surpluses and deficits among countries, the distribution of deficits is far more concentrated than that of surpluses. A striking fact in global imbalances is that the United States has always been the primary deficit country, with its deficit accounting for the vast majority of the total trade deficits of all countries. Outside of the U.S., no other country has maintained a large-scale trade deficit for an extended period. It is no exaggeration to say that the global imbalances of the past 40 years are largely the story of the U.S. continuously purchasing goods from surplus countries

In this process, the United States continuously creates dollars to pay for its imported goods, allowing dollars to flow to the world through America's trade deficit. The dollars held by other countries are then reinvested into the U.S. financial markets to purchase American financial assets, resulting in the return of dollars to the U.S. Therefore, in the context of global imbalance, accompanying the global flow of goods is the global circulation of dollars—dollars flow out of the U.S. through its purchases of foreign goods and return to the U.S. through foreign investments in the U.S. financial markets. In the process of globalization, the transnational flow of global goods and the global circulation of dollars are two sides of the same coin.

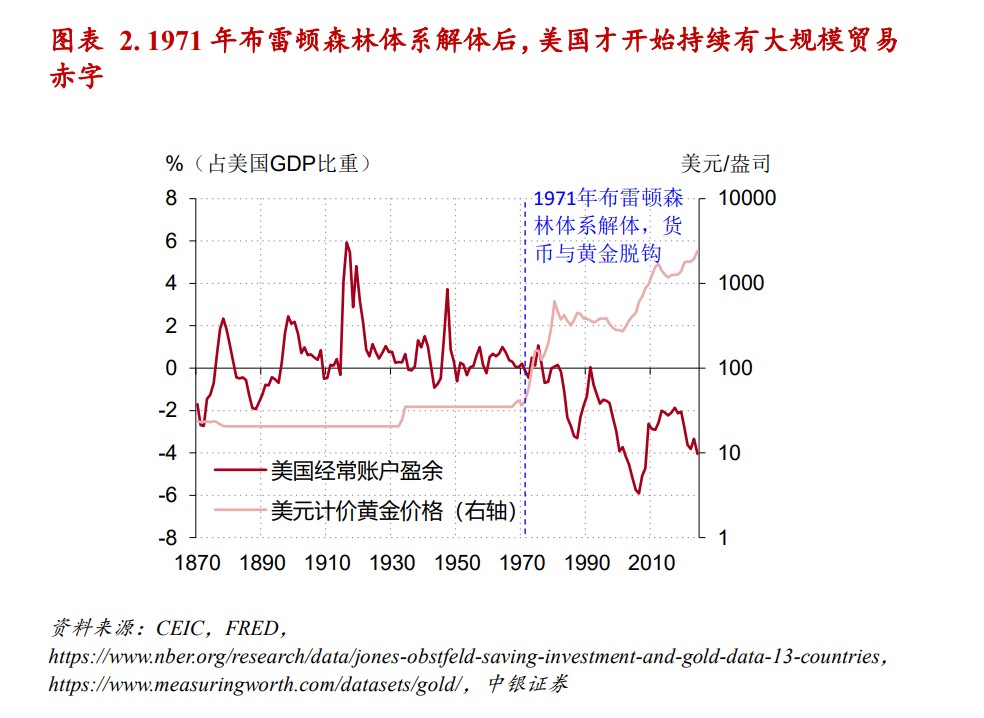

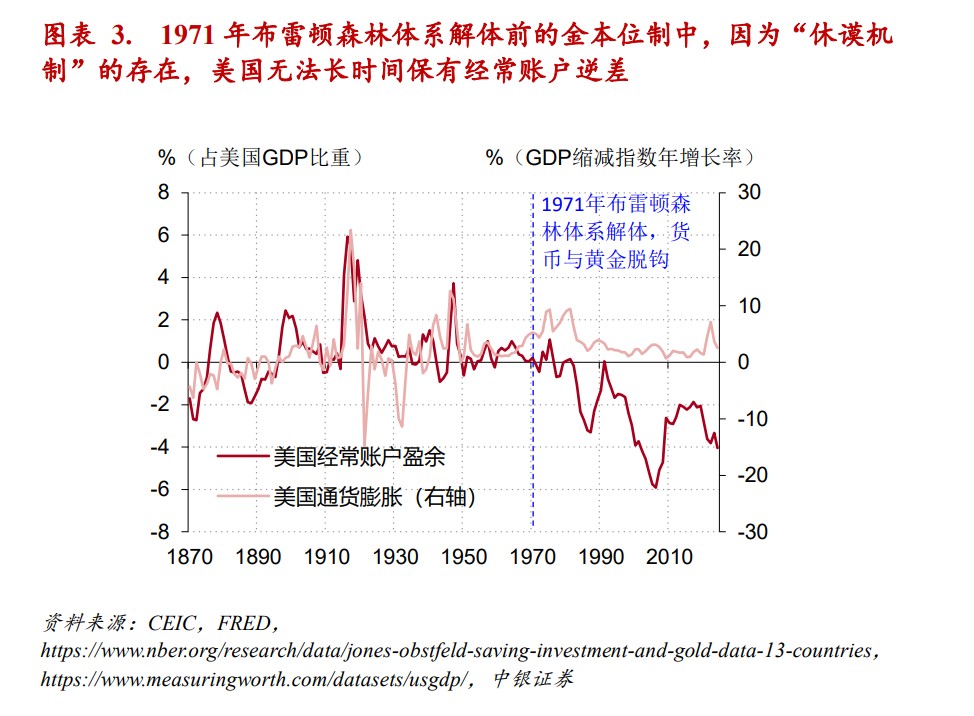

Although global imbalance has persisted for over 40 years, this situation is merely a "new phenomenon" in the history of human economic and social development. Before the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971, when the dollar was decoupled from gold, the United States did not have a long-term sustained trade deficit. Moreover, not only did the U.S. not have one, but other countries did not either. From a temporal perspective, the continuous significant rise in the price of gold denominated in dollars after the collapse of the Bretton Woods System coincides clearly with the emergence and persistence of the U.S. trade deficit, and this is not coincidental. It was precisely the decoupling of the dollar from gold in 1971 that ushered the world economy into the era of the Fiat Money System, making global imbalance possible. One could even say that between global imbalance and the global circulation of dollars, the latter is the cause and the former is the effect—the global circulation of dollars has spawned global imbalance. To understand this, a review of the evolution of the international monetary system is necessary.

Evolution of the International Monetary System

From the early 20th century to the present, the international monetary system has undergone three major stages: the Gold Standard before World War I, the Gold-exchange Standard after World War I until 1971, and the Fiat Money System from 1971 to the present.

The first stage is the Gold Standard period before World War I. Before World War I, Western industrial countries led by the UK and the U.S. generally adopted the Gold Standard. Under the Gold Standard, gold served as currency, and the currencies issued by various countries were essentially "gold-backed," with fixed exchange rates to gold. Governments of various countries committed to ensuring the free convertibility of their currencies to gold at fixed exchange rates. Under the Gold Standard, the amount of currency a government could issue was directly tied to the amount of gold it held. Since the currencies of various countries were linked to gold, fixed exchange rates automatically formed between them, known as "Gold Parity." For example, in the early 20th century, 1 British pound was equivalent to 7.32238 grams of gold, while 1 German mark was equivalent to 0.358423 grams of gold. This made the exchange rate between the pound and the mark automatically about 1 pound for approximately 20.43 marks (≈7.32238÷0.358423).

The second phase was during the gold exchange standard period in 1971, towards the end of World War I. The outbreak of World War I ended the gold standard. During the war, countries issued large amounts of currency to pay for military expenses, making it impossible to maintain the peg between their currencies and gold. After World War I ended, Western countries attempted to return to the gold standard. However, many countries had consumed large amounts of gold during the war, resulting in insufficient gold reserves post-war. To address this issue, Western countries established the "gold exchange standard" after World War I. Under this system, only the British pound and the US dollar were directly pegged to gold—Britain and the US needed to maintain sufficient gold reserves to ensure the free convertibility of the pound and dollar with gold. Other countries only needed to hold pounds and dollars, ensuring their currencies could be freely exchanged with the pound or dollar at fixed exchange rates. This is known as the "new gold standard." However, under the impact of the 1929 Great Depression, the "new gold standard" also collapsed. Even Britain ended the peg between the pound and gold in 1931.

In July 1944, as World War II was nearing victory, representatives from 44 anti-fascist allied countries signed an agreement in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, USA, establishing the post-war international monetary system, known as the "Bretton Woods System"—a gold exchange standard centered around the US dollar. In this system, only the dollar was pegged to gold. The US government promised to exchange 1 ounce of gold for 35 dollars, ensuring the free convertibility between the dollar and gold. Other countries maintained sufficient dollar reserves to ensure their currencies could be freely exchanged with the dollar at national exchange rates. Thus, the dollar became the world's primary reserve currency.

For the US to maintain the peg between the dollar and gold, the amount of dollars issued must correspond to the US's gold reserves and not exceed them. However, after World War II, US fiscal discipline gradually loosened. This situation worsened after the US entered the Vietnam War in the 1960s. To cope with increasing fiscal expenditures, the US excessively issued dollars, thereby threatening the peg between the dollar and gold.

Hume Mechanism

Under the gold standard, there cannot be a long-term persistent imbalance in the gold flow. This is because the gold standard includes the "Price-Specie Flow Mechanism," which automatically eliminates trade surpluses and deficits among countries. This mechanism was first discussed by Scottish philosopher David Hume in his 1752 work "Of the Balance of Trade," hence it is also called the "Hume Mechanism." The mechanism operates as follows: under the gold standard, gold serves as both the domestic currency of countries and as an international payment tool Trade surplus countries earn gold from other countries due to their surplus, which increases the domestic money supply (inflation), raises prices, and subsequently weakens the competitiveness of the country's goods in the international market, suppressing exports. At the same time, higher domestic price levels will also stimulate imports. Thus, the surplus of surplus countries will automatically shrink due to the inflow of gold. Conversely, trade deficit countries will experience domestic deflation and falling prices due to the outflow of gold, which stimulates exports, suppresses imports, and compresses the trade deficit.

In the long historical data of the U.S. economy, clear evidence of the "Hume mechanism" can be seen at work. In the 100 years leading up to the dissolution of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, there was a significant positive correlation between the domestic price level and the U.S. current account surplus (a broader measure of trade surplus): when the U.S. current account surplus was larger, domestic prices rose faster; when there was a current account deficit, domestic prices rose more slowly, or even experienced negative growth. The existence of this "Hume mechanism," where domestic prices change due to fluctuations in trade surplus, was the main reason why the U.S. could not sustain a trade deficit before 1971. However, after the dollar was detached from gold in 1971, the issuance of dollars was no longer limited by the amount of gold the U.S. held. The U.S. could create dollars at will, thus avoiding domestic deflation due to trade deficits. Since 1971, the U.S. has maintained a large trade deficit for a long time, while domestic prices have continued to grow positively, even experiencing periods of high inflation. This is a manifestation of the failure of the "Hume mechanism." With the "Hume mechanism" no longer in effect, the U.S. could maintain a trade deficit for an extended period, leading to global imbalances.

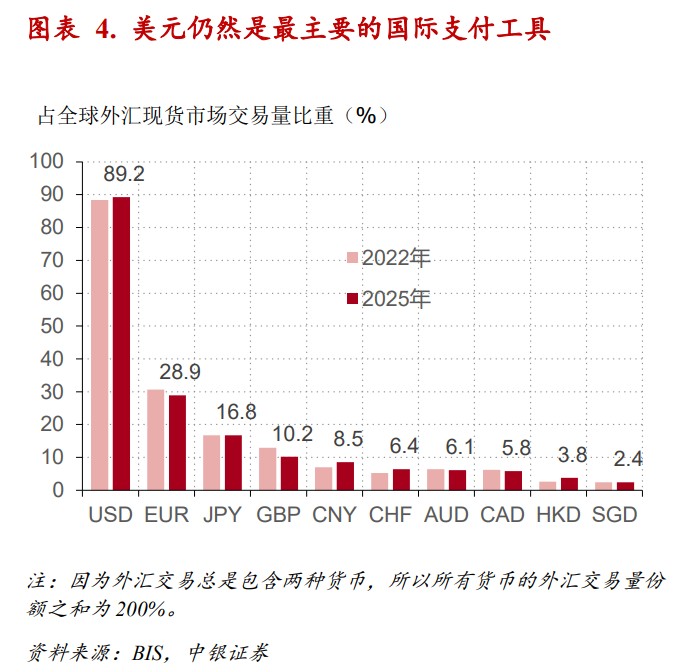

To note, using a currency created by one's own country to pay for its trade deficit is a privilege granted to the U.S. by the dollar, which other countries cannot imitate. At the end of World War II, the U.S. had the strongest economy and military power in the world. Therefore, in the Bretton Woods system it led to establish, the dollar naturally became the primary international reserve currency and payment tool. Although the Bretton Woods system has been dissolved for more than 50 years, the dollar remains the primary international payment tool. In 2025, transactions involving the dollar still accounted for nearly 90% of the total trading volume in global foreign exchange spot trading. The dollar's hegemony comes partly from the fact that the U.S. still possesses the strongest comprehensive national power in the world, and partly from path dependence in international economic and trade activities.

Other countries outside the U.S. cannot directly use their own currencies for international payments and must rely on international payment tools (mainly the dollar) for international trade settlements. In other words, other countries cannot arbitrarily create international payment tools Therefore, for other countries with trade deficits outside of the United States, a certain transformed adjustment mechanism still holds. If these countries have a trade deficit that is too large and lasts too long, leading to their external debt exceeding the number of international payment instruments they possess, an international balance of payments crisis (i.e., a foreign debt crisis) will erupt. An international balance of payments crisis will forcibly compress the trade deficits of these countries. Since only the United States can avoid the constraints of an international balance of payments crisis, the trade deficits in global imbalances mainly come from the United States.

The Global Circulation of the Dollar Driven by the "Jamaica System"

One hand cannot clap alone; if there are only trade deficits from the United States without trade surpluses from surplus countries, there would be no global imbalance. For two reasons, the surpluses of global surplus countries have continued to accumulate over the past 40 years of globalization.

One reason is that surplus countries have a sustained willingness to accumulate surpluses. This has multiple reasons, and the situations of different surplus countries vary. For example, oil-exporting countries typically do not use all the foreign exchange earned from oil exports for imports, but instead retain a large portion for overseas investment to prepare for the depletion of oil resources, thus forming a long-term trade surplus for oil-exporting countries. East Asian countries, influenced by Confucian culture, usually have a higher savings rate, and therefore also invest a portion of their domestic savings overseas through trade surpluses. In addition to being influenced by a frugal culture, our country has a long-term savings surplus due to the domestic income distribution structure, resulting in a sustained trade surplus (refer to the author's discussion in the article "The Dialectics of Supply and Demand" published in April 2025).

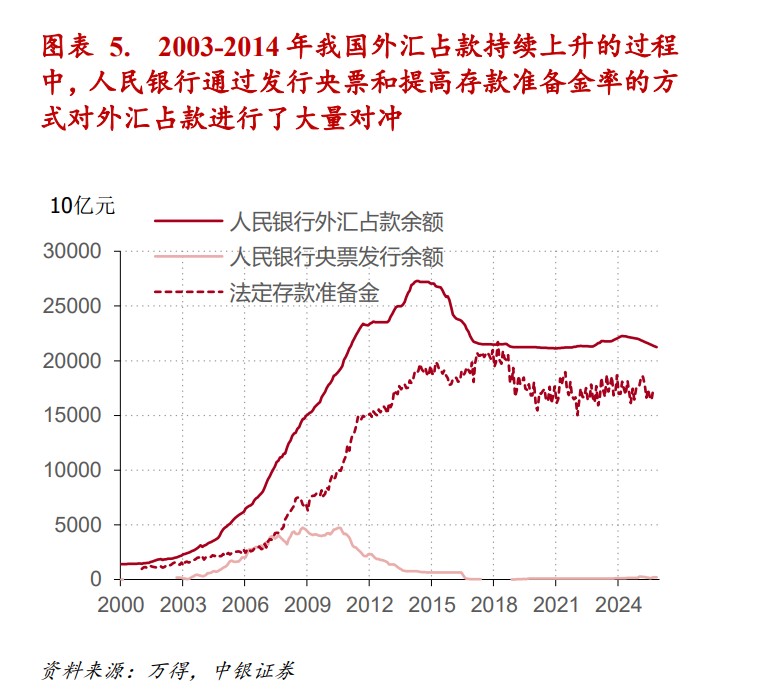

The second reason is that under the current "Jamaica System," trade surplus countries can avoid the adjustment pressure of the "adjustment mechanism" through "sterilization operations." Even within the Jamaica System, surplus countries earn international payment instruments (mainly dollars) due to trade surpluses. If enterprises and residents in surplus countries that earn dollars exchange them for local currency, it will lead to an expansion of domestic money supply and inflation. The domestic currency released passively by the central bank of surplus countries during the foreign exchange settlement (exchanging foreign exchange for local currency) is known as "foreign exchange occupation." Between 2003 and 2014, our country experienced a significant trade surplus, leading the People's Bank of China to issue over 20 trillion yuan in foreign exchange occupation. However, the central bank of surplus countries has ways to withdraw these issued foreign exchange occupations to avoid domestic inflation. During the same period from 2003 to 2014, the People's Bank of China first replaced the foreign exchange occupations held by commercial banks by issuing central bank bills (CBBs), and later continuously raised the reserve requirement ratio to lock in the foreign exchange occupations held by commercial banks. Through these two sterilization operations of issuing CBBs and raising the reserve requirement ratio, the People's Bank of China hedged against the issuance of foreign exchange occupations during the massive inflow of foreign exchange due to trade surpluses, ensuring the stability of domestic inflation.

In summary, within the Jamaica system, the trade deficit of the United States (as the issuer of the international reserve currency) and the trade surplus of surplus countries will not be automatically corrected through the flow of international payment instruments as they would under the gold standard. This makes global imbalances possible. We can even say that global imbalances are a byproduct of the unlimited nominal currency creation capacity brought about by the fiat currency system after human society entered it. In the fiat currency system, the United States can purchase goods from other countries using value symbols (dollars) that it creates at no cost, thereby enjoying a higher level of welfare. At the same time, countries like ours, which have insufficient domestic demand, can use trade surpluses to compensate for the lack of internal demand through external demand, thus achieving a higher economic growth rate. In this process, the global circulation of the dollar, which arose from the "Jamaica system," has played an indispensable role.

In summary, within the Jamaica system, the trade deficit of the United States (as the issuer of the international reserve currency) and the trade surplus of surplus countries will not be automatically corrected through the flow of international payment instruments as they would under the gold standard. This makes global imbalances possible. We can even say that global imbalances are a byproduct of the unlimited nominal currency creation capacity brought about by the fiat currency system after human society entered it. In the fiat currency system, the United States can purchase goods from other countries using value symbols (dollars) that it creates at no cost, thereby enjoying a higher level of welfare. At the same time, countries like ours, which have insufficient domestic demand, can use trade surpluses to compensate for the lack of internal demand through external demand, thus achieving a higher economic growth rate. In this process, the global circulation of the dollar, which arose from the "Jamaica system," has played an indispensable role.

The Backlash of the Dollar on the United States

In the global circulation of the dollar, both deficit countries (the United States) and surplus countries are beneficiaries, thus fostering the prosperity of the large circulation. However, it is precisely within this prosperous scenario that the seeds of decline for the large circulation are hidden.

Theoretically, the genes for the decline of the global circulation of the dollar may originate from the United States or from surplus countries. In the past, scholars were more concerned about the risk that surplus countries would no longer accept more dollars, leading to the termination of the dollar's large circulation. After all, for surplus countries, accepting dollars means subsidizing the United States and allowing it to take advantage of its own resources. However, it now appears that the demand for dollars from surplus countries remains strong, but the seeds of decline for the global circulation of the dollar are sprouting in the United States.

There is no doubt that the United States is a beneficiary of the global circulation of the dollar. The trade deficit of the United States corresponds to the outflow of dollars from the U.S., which can be seen as a "seigniorage" tax that the U.S. levies on the world using dollars. In 2024, the U.S. current account deficit is approaching $1.2 trillion, accounting for 4% of that year's GDP. From 2001 to 2024, the cumulative current account deficit of the United States has approached an astonishing $14 trillion. However, things are dialectical; where there is benefit, there is also harm. While the United States exploits the world's resources through the dollar's large circulation, it also bears the backlash that the dollar brings to the U.S.

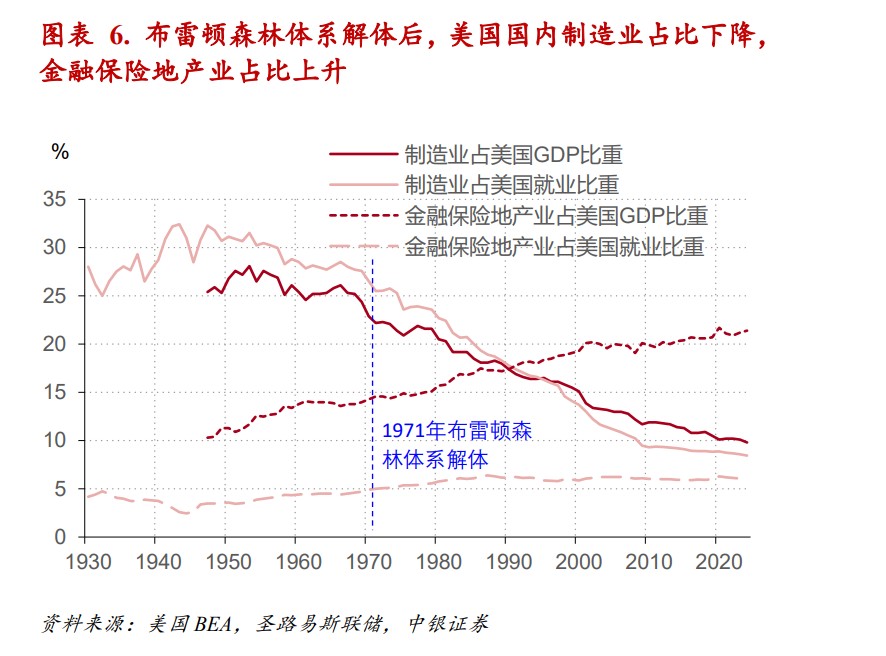

The greatest backlash of the dollar on the United States is the decline of manufacturing and the hollowing out of industries. After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, U.S. manufacturing clearly declined. The proportion of manufacturing in U.S. GDP fell from 22% in 1971 to 10% in 2024. The proportion of manufacturing employment in total domestic employment in the United States remained stable at over 25% for the 40 years prior to 1971. By 2024, this proportion had dropped to 8%. The fundamental reason for the decline of U.S. manufacturing and the hollowing out of industries is the dollar—under the Jamaica system, the United States has suffered from "Dutch disease" due to the dollar.

The so-called Dutch disease refers to the phenomenon where the abnormal prosperity of a primary product sector in a country's economy leads to the decline of other sectors. In the 1960s, the Netherlands, already a manufacturing powerhouse, discovered large oil fields in the North Sea. The Dutch economy prospered due to the subsequent large exports of oil and natural gas. However, alongside this economic prosperity was the decline of Dutch manufacturing The reasoning behind this is not complicated. When a country can easily make money by selling energy, it becomes difficult for the manufacturing industry, which requires hard and continuous investment, to develop. When residents of a country can easily find high-paying jobs in the energy sector, their willingness to engage in the labor-intensive manufacturing industry decreases. Thus, the prosperity of energy exports exerts a significant squeeze on other industries (especially manufacturing), leading to their decline.

Typically, the Dutch disease occurs in small countries. This is because only in small countries can the energy sector's share of the economy rise to a level that causes the manufacturing industry to decline. The United States is a large country with a GDP close to $30 trillion. Since the beginning of the 21st century, although the shale oil revolution has doubled the U.S. oil and gas production, the share of oil and gas extraction in the U.S. GDP has only fluctuated around 1% in recent years.

The U.S. dollar's seigniorage collected globally is a much larger business than selling energy, both in terms of scale and revenue. Since 1971, the financial, insurance, and real estate sectors, which have strong financial attributes, have greatly benefited from the export of the dollar. The combined share of these three sectors in the U.S. GDP has risen from 14.6% in 1971 to 21.2% in 2023. During the same period, the total employment in the financial, insurance, and real estate sectors has changed little, only slightly increasing from 5% in 1971 to 6% in 2024. The fact that the employment share in these three sectors has increased far less than their GDP share reflects the "deindustrialization" of the U.S. economy during the dollar's export process. The rapid growth of such a large financial-related sector during the dollar's export process has exerted pressure on manufacturing. It can be said that in the past 40 years of globalization, the dollar has been the most competitive "export product" of the U.S., and the export of the dollar is the most competitive "export industry" of the U.S., which has led to the U.S. suffering from the Dutch disease due to the massive outflow of dollars. This is the biggest challenge that the global circulation of the dollar poses to the U.S.

In addition to industrial hollowing out, the dollar's global circulation (and corresponding globalization) presents another significant challenge to the U.S.: the widening income distribution gap. As mentioned earlier, the U.S. collects a large amount of seigniorage globally through the dollar each year, but it has not distributed this wealth more equitably domestically. Consequently, within the U.S., a beneficiary of globalization, there are a considerable number of "globalization losers." Whether it was the "Occupy Wall Street" movement in 2011 or the "Trump phenomenon" that emerged in the last decade, both reflect the contradictions between globalization winners and losers within the U.S. The fact that Trump was re-elected as President of the United States in 2024 indicates that the voices of globalization losers in the U.S. can no longer be ignored.

Fundamental Triffin Dilemma

In the long run, the global circulation of the dollar is unsustainable. This unsustainability stems from the contradiction between dollar hegemony and British hegemony—what I call the "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma." Before discussing it, it is necessary to introduce the "Triffin Dilemma." In 1960, Triffin predicted the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in his book "Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility." Triffin's logic was that, in the face of the increasing demand for international payment instruments from the international community, the United States had to provide dollars to the world through continuous trade deficits. However, this would cause the amount of dollars issued to exceed the support capacity of U.S. financial reserves, ultimately leading to the decoupling of the dollar from gold. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 confirmed Triffin's prediction made more than a decade earlier.

However, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system did not shake the central position of the dollar in the international monetary system. This is because, on one hand, there is a demand for international payment instruments from the international community; on the other hand, among the various possible options for international payment instruments, none has yet been able to replace the dollar. Therefore, although dollar hegemony was formed during the Bretton Woods system, it did not end with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. It was precisely after the dollar decoupled from gold that the issuance of dollars was freed from the constraints of gold, allowing for a faster growth of the dollar supply to drive the development of international trade, resulting in over 40 years of global imbalance and the global circulation of the dollar. Thus, the "Triffin Dilemma" is a problem for the dollar linked to gold, but it does not pose a significant threat to dollar hegemony. The operation of the international economy over the past half-century has shown that dollar hegemony is not based on the dollar's link to gold.

In recent years, some in the international academic community have proposed the concept of the "New Triffin Dilemma" to explain the contradiction between (the outflow of) dollars and the fiscal sustainability of the United States. Driven by the global circulation of the dollar, U.S. government debt and external debt have continued to accumulate, raising market concerns about the sustainability of U.S. debt. However, as I discussed in my article "Where Does Dalio's Understanding of National Debt Go Wrong?" published in July 2025, while U.S. fiscal sustainability is built on dollar hegemony, dollar hegemony will not be lost due to an increase in U.S. government debt. In other words, there is no fundamental contradiction between dollar hegemony and the accumulation of U.S. debt; the "New Triffin Dilemma" is not a real dilemma.

For dollar hegemony, the truly fatal issue is the "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma." The status of the dollar as the primary international reserve currency (dollar hegemony) was formed during the Bretton Woods period and has certain path dependency components. However, the fundamental prerequisite for dollar hegemony is still U.S. hegemony. At the end of World War II, the United States, with its comprehensive national power far exceeding that of other countries, made the dollar the core of the international monetary system. However, a United States with hollowed-out domestic industries and declining manufacturing is unlikely to maintain its comprehensive national power advantage in the long term and is likely to ultimately lose its hegemony. The loss of U.S. hegemony will eventually lead to the loss of dollar hegemony. This is the "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma" that the United States is currently facing, namely the contradiction between U.S. hegemony and dollar hegemony—U.S. hegemony created dollar hegemony, but dollar hegemony, in turn, may erode U.S. hegemony and ultimately lead to the loss of dollar hegemony. This contradiction is fundamental and cannot be resolved through a workaround like the "Triffin Dilemma" by decoupling the dollar from gold, so the author refers to it as the "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma."

The "Fundamental Triffin Dilemma," while indicating the decline of the dollar's global circulation, will not happen immediately but will unfold slowly over the next few decades. This is because the international community has a huge ongoing demand for international payment mechanisms. This demand arises not only from the growth of international trade but also from the need for international safe assets by surplus countries with excess savings. Furthermore, among the five potential challengers to the dollar's status, none currently possess the strength to replace the dollar. To keep this article concise, we will only highlight the core conclusions.

First, returning to the "gold standard" and using gold again as an international payment tool is completely impossible. Re-linking currency to gold would mean that the money supply would once again be constrained by the low growth rate of gold, leading to long-term deflation in human society and the loss of monetary policy as an important tool for macroeconomic regulation. Second, the United States has a veto power in the IMF and will certainly not allow SDRs issued by the IMF to replace the dollar. Third, issuing a supranational currency to replace the dollar must overcome significant international political obstacles, which cannot be considered in the short term (the difficulties can be understood by looking at the history of the euro's development). Fourth, considering that the United States still possesses the strongest comprehensive national power, along with the "incumbent advantage" of the dollar as the dominant international reserve currency, no other sovereign country's currency can currently replace the dollar. Fifth, cryptocurrencies based on blockchain technology face an irreconcilable contradiction between "decentralization" and "performance," making this technological route unlikely to become a widely used payment tool.

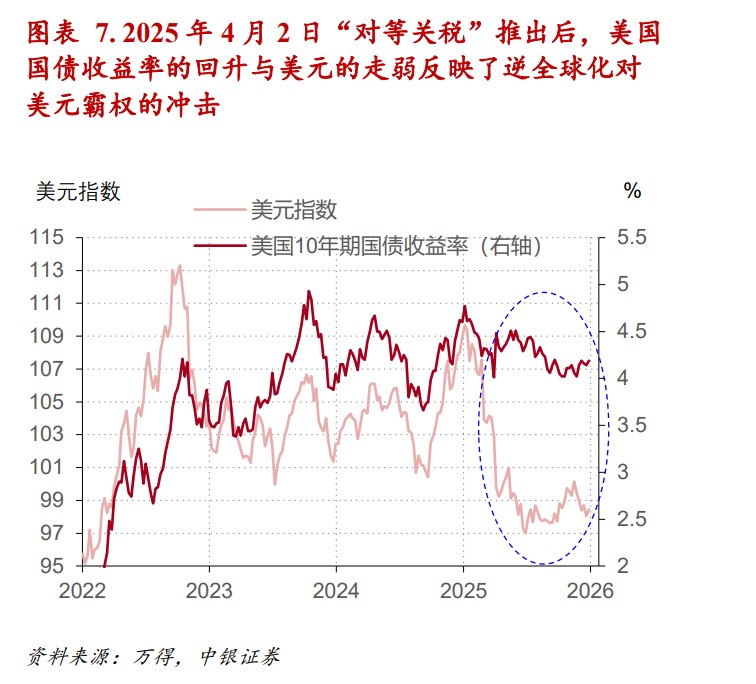

However, although the decline of the dollar's global circulation will be a long-term process, its effects are already reflected in the current international market. The "Reciprocal Tariff" policy launched by the United States on April 2, 2025, is a landmark event that reflects a turning point from prosperity to decline in the dollar's global circulation, driven by the wave of de-globalization in the United States. At this turning point, the anticipated changes have significantly impacted the prices of assets such as the dollar and gold.

The United States' "Reciprocal Tariff" Policy

In the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Trump made a comeback and was re-elected as President of the United States. During his first term from 2017 to 2021, President Trump fully revealed his inclination towards trade protectionism and initiated the first round of trade friction with China in 2018. In his second term starting in 2025, President Trump quickly launched large-scale de-globalization policies, introducing the "Reciprocal Tariff" policy on April 2, 2025, which imposed tariffs on countries around the world.

The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) announced in April 2025 the "Reciprocal Tariff Calculations," claiming that tariffs and non-tariff barriers from other countries hindered U.S. exports, resulting in a long-standing large trade deficit for the United States, and that "American consumer demand has been attracted to the global economy." Since 1997, more than 90,000 American factories have closed, and the U.S. manufacturing workforce has decreased by over 6.6 million jobs, a decline of more than one-third from its peak.

According to the announcement from the Office of the United States Trade Representative, the U.S. government has misidentified the cause of the trade deficit. As previously discussed, the main reason for the persistent trade deficit and decline of domestic manufacturing in the U.S. over the past 40 years of globalization is the massive outflow of dollars. With the support of dollars, many tradable goods are "cheaper to buy than to make" for the U.S. If the dollars flowing out of the U.S. are also considered U.S. export products, then U.S. trade is actually balanced. The root of the U.S. trade deficit does not lie in the trade protectionist barriers imposed by other countries, but in the dollar exports that are not counted in trade data, which crowd out the share of goods exports that are counted. In other words, the dollar has caused the U.S. to lose its comparative advantage in the real economy, leading to the decline of the manufacturing sector.

Although the U.S. has misidentified the issue, the "reciprocal tariffs" prescription proposed by the U.S. government is not without reason. Higher import tariffs imposed by the U.S. will indeed reduce imports and compress the trade deficit. As mentioned earlier, the U.S. trade deficit corresponds to the "dollar exports" of the U.S. If the trade deficit is compressed, dollar exports will naturally decrease, and the pressure of dollar exports on the U.S. real economy will also correspondingly decline, thus benefiting the return of manufacturing to the U.S. In the face of the challenges of globalization and the backlash of the dollar, using policies like "reciprocal tariffs" to steer globalization is not the best choice for the U.S., but it is a relatively acceptable path.

Therefore, the "reciprocal tariffs" policy can be seen as a measure by the U.S. government to curb the significant outflow of dollars globally, reflecting the U.S. government's choice to consolidate its hegemony at the cost of sacrificing dollar dominance when faced with the "fundamental Triffin dilemma." In this sense, "reciprocal tariffs" are a symbolic event marking the transition of dollar dominance from prosperity to decline.

Some may wonder why the "reciprocal tariffs" that curb dollar exports would sacrifice dollar hegemony. In fact, the U.S. government has not made any statements indicating a willingness to abandon dollar hegemony. In July 2024, presidential candidate Trump proposed 20 campaign promises, one of which is to "maintain the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency." The U.S. government's introduction of the "reciprocal tariffs" policy aims to guide manufacturing back to the U.S., and its intention should not be to harm the dollar's position in the international monetary system. However, whether the U.S. government realizes it or not, the introduction of the "reciprocal tariffs" policy has indeed made a choice favoring the strength of the U.S. real economy over dollar hegemony, which will ultimately cost the dollar hegemony.

Studying the international financial market's reaction to the "reciprocal tariffs" policy can help us understand this point. After the introduction of "reciprocal tariffs" in April 2025, the dollar index, which measures the strength of the dollar, fell sharply and has remained weak since then. During the same period, the dollar index and U.S. Treasury yields showed a clear negative correlation (as the dollar weakened, Treasury yields rose), contrasting sharply with the positive correlation observed in the previous three years Understanding why the U.S. Dollar Index and U.S. Treasury yields have such fluctuations allows us to comprehend why reverse globalization policies like "reciprocal tariffs" can undermine the dollar's hegemony.

Understanding "Reciprocal Tariffs" from Market Performance

In the global circulation of the dollar, the dollar provides the U.S. with goods from other countries, thereby suppressing domestic inflation levels while also bringing surplus savings from abroad, which supports the accumulation of domestic debt in the U.S. This can be seen in the experiences of dollars participating in the global circulation. As for the larger number of dollars that only circulate domestically within the U.S., they do not significantly impact our understanding of the current issues, so they will not be discussed here.

The dollars participating in the global circulation are created by the U.S. financial system. These created currencies first flow into the U.S. economy, held by various economic entities (households, businesses, and the government) within the U.S. economy. Subsequently, this portion of dollars flows abroad through these economic entities' purchases of foreign goods, simultaneously bringing foreign goods into the U.S., thereby increasing the supply of goods domestically and suppressing inflation levels in the U.S. Countries earning dollars will also use the dollars they hold to pay for their imports. Ultimately, the dollars flowing to other countries will be held by those with trade surpluses—because surplus countries spend fewer dollars on imports than they earn through exports, leading to an accumulation of dollar positions. The dollar positions held by surplus countries correspond to their surplus savings (savings not used by the surplus countries themselves). Since the U.S. has the largest and most developed financial market in the world, surplus countries will mostly invest their dollar positions into the U.S. financial market, purchasing U.S. financial assets. In this way, the surplus savings of surplus countries flow to the U.S., supporting the accumulation of domestic debt.

"Reciprocal tariffs" help alleviate the hollowing out of domestic industries in the U.S., thereby maintaining U.S. hegemony. However, for "reciprocal tariffs" to achieve the desired effect, a transformation of the U.S. domestic economic structure is needed to complement it. In the imbalanced macroeconomic environment of high consumption, low savings, and excessive domestic demand in the U.S., it is precisely the global circulation of the dollar that suppresses U.S. inflation, supports U.S. debt, and thus maintains the supply-demand balance in both the goods and savings markets in the U.S. Until the U.S. economy successfully implements a structural transformation to reduce consumption, increase savings, and suppress domestic demand, forcibly compressing the global circulation of the dollar through "reciprocal tariffs" will tighten the bottlenecks of U.S. goods supply and savings supply, leading to rising inflation in the U.S. and risks emerging in debt.

After the introduction of the "reciprocal tariffs" policy, U.S. domestic policies have not made efforts towards a structural transformation aimed at suppressing consumption, increasing savings, and reducing domestic demand. The "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" passed in July 2025 will further expand the U.S. fiscal deficit, rapidly increasing the scale of government debt, thereby further stimulating domestic demand in the U.S. In the absence of complementary policies for structural transformation in the U.S. economy, the "reciprocal tariffs" policy will expose U.S. debt to risks, leading to a decline in Treasury prices If the dollars that previously participated in the global circulation, under the influence of "reciprocal tariffs," turn to only do domestic circulation in the United States, and the domestic savings rate in the U.S. does not increase accordingly to absorb these dollars, then these dollars will push up the demand for domestic goods in the U.S., thereby driving up domestic inflation. After inflation rises, the Federal Reserve will have to tighten monetary policy and withdraw money. This will lead to a decrease in buying in the U.S. Treasury market, causing Treasury prices to fall and yields to rise. The key here is whether the dollars purchasing U.S. Treasuries have significantly circulated abroad; the impact on Treasury prices is completely different: dollars that participated in the global circulation brought back savings from other countries to the U.S., thus lowering Treasury yields; dollars that did not participate in the global circulation did not bring in goods and savings from other countries, thus pushing up domestic inflation and Treasury yields in the U.S.

The demand for dollars in the international community largely comes from surplus countries' need to invest their excess savings, manifested as a demand for safe assets. In the past, U.S. Treasuries were considered one of the safest assets, thus attracting a large amount of overseas savings to flow into them. However, as "reciprocal tariffs" suppressed the global circulation of dollars and led to risks in U.S. domestic debt, U.S. Treasuries are no longer as safe as they used to be. This has caused some international funds to withdraw from dollar assets, leading to a depreciation of the dollar. This is the main reason for the weakening of the dollar index since April 2025.

Before April 2025, the positive correlation between the dollar index and U.S. Treasury yields was due to the relatively stable confidence in dollar assets in the international market, with U.S. domestic monetary policy dominating the market. The Federal Reserve is both a demand side for U.S. Treasuries and a supply side for international dollars. When the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy, it means a decrease in demand for Treasuries and a reduction in the supply of international dollars, which will lead to an increase in Treasury yields (falling Treasury prices) and a tightening of the dollar supply. Conversely, when the Federal Reserve loosens monetary policy, it will bring about a bullish trend in Treasury yields and the dollar.

After April 2025, as "reciprocal tariffs" disrupted the global circulation of dollars and reduced global investors' confidence and demand for dollar assets, the flow of international funds became the dominant factor affecting Treasury and dollar prices. Funds withdrawing from the U.S. led to a decline in the dollar, a drop in Treasury prices, and an increase in Treasury yields, thus forming a negative correlation between the dollar index and Treasury yields.

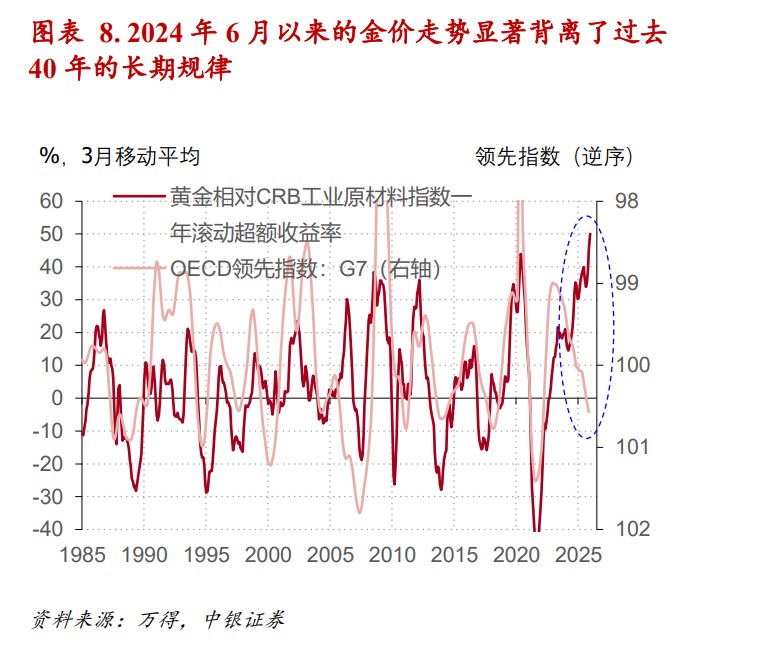

The abnormally high gold prices in 2025 are also related to the turning point of the global circulation of dollars. Typically, gold is a special commodity with safe-haven attributes, and gold prices have a clear counter-cyclical nature: when the global economy is booming, gold prices tend to underperform industrial raw material prices; when the global economy weakens, gold prices tend to outperform industrial raw material prices. Over the past 40 years, this counter-cyclical nature of gold prices has been quite significant. However, the situation began to change in June 2024. In the more than a year since then, the international economic prosperity, measured by the leading index of the seven major industrial countries (OECD), has significantly increased, reflecting an overall improvement in international economic prosperity. According to the previous 40 years of experience, gold prices should underperform industrial raw material prices at this time. However, the opposite has occurred; during this period, the relative surge in gold prices compared to industrial raw material prices has not decreased but increased, even reaching a new high in 40 years, completely breaking the historical experience of the past 40 years

The abnormal surge in gold prices reflects a turning point in the global circulation of the US dollar. Although there is still no alternative to the dollar among various international payment tools (including gold), the decline in confidence in the dollar will still affect the prices of various assets. For international investors, while no substitute for the dollar has been found, it is reasonable to reduce dollar assets and increase gold in their asset allocation. The unusual rise in gold prices should stem from this.

The Decline of the Global Circulation of the US Dollar

More than a decade ago, when the global imbalance became significantly pronounced, some in the international economics community worried that surplus countries would stop providing financing to the US, leading to a disorderly contraction of the global circulation of the dollar. Later, some even argued that if surplus countries sold off US Treasury bonds, it would be a "financial nuclear weapon" to combat global imbalances. However, recent developments in the international economy indicate that the weak link in the global circulation of the dollar lies not with the surplus countries, but with the US itself. Now, it is not the surplus countries selling off and abandoning the dollar, but the US itself imposing restrictions on the outflow of the dollar.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, the decline of the global circulation of the dollar is a long-term, slow, and even tumultuous process. For a considerable time to come, the flow of dollars from the US to trade surplus countries and then back to the US will continue. However, the rising discontent among "globalization losers" in the US, the rise of domestic protectionist tendencies, the potential re-election of President Trump, and the introduction of "reciprocal tariffs" all indicate that the US's attitude towards the global circulation of the dollar has quietly changed. Currently, we are witnessing a significant turning point in the global circulation of the dollar. The curvature of the turn may be gentle, but the expected changes at the turning point can be quite pronounced. The recent changes in the trends of the dollar and gold prices have already indicated this.

Some may ask whether the current fervent wave of artificial intelligence (AI) development will change the above conclusion, providing new impetus to the global circulation of the dollar, or completely overturning the current international monetary system, thus rendering the previous analysis completely invalid? In an interview at the end of 2025, Elon Musk even suggested that AI could make money obsolete. He said, "In a future where anyone can have anything, you no longer need money as a database for labor distribution. If AI and robots are powerful enough to meet everyone's needs, then money becomes unnecessary." In a world where money does not exist, the global circulation of the dollar naturally cannot be discussed.

The impact of AI development on national and international economies deserves a dedicated article for analysis, which cannot be clearly explained in just a few words here. The author will only provide two summary conclusions. First, AI may indeed lead to another leap in human production capacity, but how products should be distributed remains a challenge. AI will not provide everyone with a magical pocket where they can have whatever they want, but is more likely to give rise to some "super factories" with enormous production capacity When allocating products from these super factories, currency is still needed. Secondly, among countries around the world, it is not only the United States that has AI technology. Even if other countries' AI technology lags behind that of the United States, the gap is not far. While AI technology drives the expansion of productivity in various countries, the dollar still causes the United States to lack a comparative advantage in commodity production—no matter how strong AI is, it cannot create something out of nothing; however, the dollar can be created "out of thin air." Therefore, unless AI truly develops to a point where material production is extremely abundant, and everyone can access products as easily as breathing (the author highly doubts the realism of such a scenario), the logic discussed earlier remains valid. It is worth mentioning that if a scenario of extreme material abundance does indeed come about due to AI, then even the United States must demand some form of communism; otherwise, the widening income distribution gap caused by "machines replacing labor" will provoke social unrest. This is a later discussion and will not be elaborated on here.

Lessons for Our Country from the Rise and Fall of the Dollar's Global Circulation

From the rise and fall of the dollar's global circulation, our country can draw three lessons.

First, in the long term, the internationalization of the renminbi should not aim to replace the dollar or establish renminbi hegemony. From the analysis above, we can see that under the fiat currency system, using a country's sovereign currency as an international reserve currency is a double-edged sword for that sovereign country. On one hand, this country can levy seigniorage on the world by providing currency supply, thus enjoying a welfare level higher than its own production capacity; on the other hand, it will also squeeze domestic industries due to currency outflow, ultimately harming its own production capacity. The expansion of production capacity is the foundation for a country's sustainable development and maintenance of its international status. Printing money to buy foreign goods may yield short-term gains, but it will erode the foundation of long-term national development.

In the past 15 years, our country's "renminbi internationalization" strategy has made significant progress. According to statistics from the Bank for International Settlements, in 2010, the proportion of transactions involving the renminbi in global foreign exchange trading was only 0.9%. By 2025, this proportion is expected to rise to 8.5%. Looking ahead, as our comprehensive national strength and international influence continue to grow, the internationalization of the renminbi will continue to achieve breakthroughs. However, our country should not repeat the mistakes of the United States by sacrificing long-term development for short-term interests. The internationalization of the renminbi should not aim to replace the dollar. Regardless of which country's currency is above the dollar's current position, it will bring backlash to the currency issuing country, leading to the "fundamental Triffin dilemma." The dollar's current status as the primary international reserve currency is a sweet trap that the renminbi needs to avoid.

In March 2009, then-Governor of the People's Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan published an article titled "Thoughts on Reforming the International Monetary System," arguing that "creating an international reserve currency that is decoupled from sovereign countries and can maintain long-term stability in value, thereby avoiding the inherent flaws of sovereign credit currencies as reserve currencies, is the ideal goal of international monetary system reform." Zhou Xiaochuan's viewpoint shares common ground with the blueprint designed by Keynes for the post-World War II international monetary system, which can largely avoid the drawbacks of using sovereign currencies as international reserve currencies In terms of the long-term reform direction of the international monetary system, our country should adhere to this viewpoint, rather than establishing the hegemony of the Renminbi.

Currently, the globalization of the Renminbi should aim to build a backup payment channel for our foreign trade. In recent years, the U.S. government has increasingly "weaponized" the dollar, using "kicking out of the dollar payment network" as a tool to threaten other countries. In this context, our country needs to have a bottom-line mindset and prepare for the worst-case scenario. By internationalizing the Renminbi and building a Renminbi payment network, we can ensure the smooth payment channels for our foreign trade in extreme situations.

Secondly, in the medium term, our country should actively expand domestic demand and promote consumption transformation, reducing reliance on "external circulation" through a smoother "internal circulation." Our country is a beneficiary of the global dollar cycle. As early as around 2000, we experienced insufficient domestic demand and fell into a long-term deflation from 1998 to 2002. Later, driven by external demand, we emerged from deflation in 2003 and achieved rapid economic growth before the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis. In recent years, although the driving force of external demand for our economic growth has weakened, it remains an important demand-side engine for maintaining stable economic growth.

However, our country has also paid a certain price for the new growth driven by external demand. Years of trade surplus have allowed us to accumulate trillions of dollars in overseas assets. The scale of our official foreign exchange reserves alone exceeds 3 trillion dollars. A significant proportion of these should be dollar financial assets (such as U.S. Treasury bonds). These dollar financial assets are essentially value symbols created by the cost of the U.S. dollar, and fundamentally represent a subsidy that our country pays back to the U.S. with its own savings. Simply put, this is the "external circulation usage fee" that our country pays to other countries. If we can expand domestic demand, especially boost domestic consumption, we would no longer need to pay such usage fees, thereby enhancing the welfare of our domestic population. It is better for our country to subsidize its own residents rather than subsidizing foreigners.

In addition, our country has grown into a major world power and has become the world's largest manufacturing country. It is relatively easy for the world economy to drive the external demand of a small country, but it is much more difficult to drive the external demand of a large country like ours. Specifically, the U.S., as the ultimate creator of global external demand, is turning towards de-globalization, attempting to reduce its trade deficit. As the global dollar cycle declines, the external environment in which our country operates has undergone significant changes, and we can no longer expect "external circulation" to drive our demand as it did in the past few decades. Changes in the international situation require our country to shift its development model, strengthen "internal circulation," and promote consumption transformation. The author reached the same conclusion from our own logic in the article "The Logic and Path of China's Economy" published in January 2025, which can corroborate the analysis here.

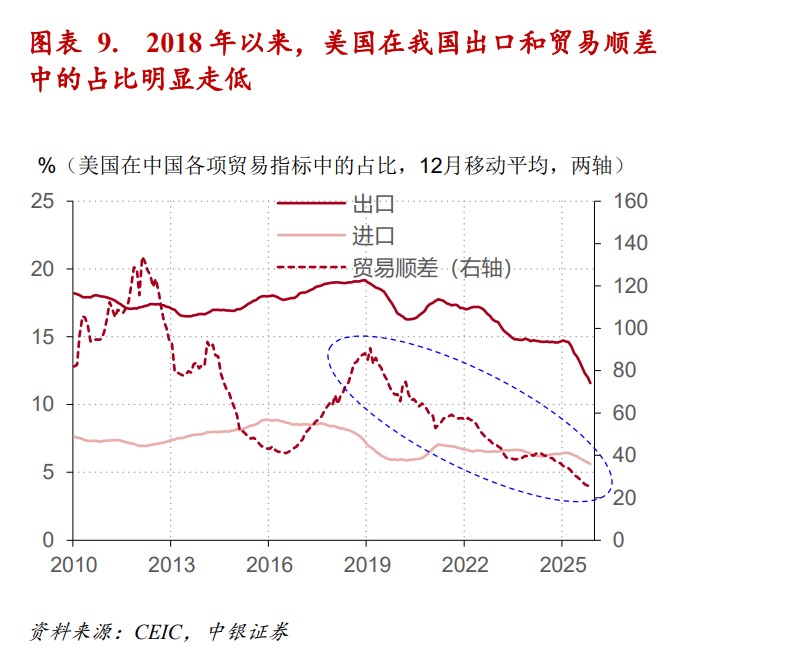

Thirdly, in the short term, our country is likely approaching the "ceiling" of external demand. Since the first round of trade friction between China and the U.S. began in 2018, it seems that the sources of our external demand have become quite diversified. Currently, direct exports to the U.S. account for 11% of our total exports, down from 19% in 2018. During the same period, the trade surplus with the U.S. accounted for 24% of our total surplus, down from 88% However, the apparent diversification of China's exports and trade surplus does not indicate a decline in the importance of the United States in China's external demand. In fact, the significance of the U.S. to China's external demand has actually increased in recent years.

First, it is important to clarify that when we refer to "external demand" in this context, we mean China's trade surplus, not the total export volume. This is because what drives China's economic growth (contributing to GDP growth) is the trade surplus rather than the total exports. In this closed economic system of the Earth, China's trade surplus corresponds to the trade deficit of other countries. The previous discussion has already indicated that under the current international monetary system, only the United States, backed by the dollar, has the ability to create large-scale trade deficits for an extended period. Other countries, constrained by international balance of payments crises, have limited capacity to create trade deficits. Therefore, ultimately, China's external demand mainly comes from the U.S. deficit.

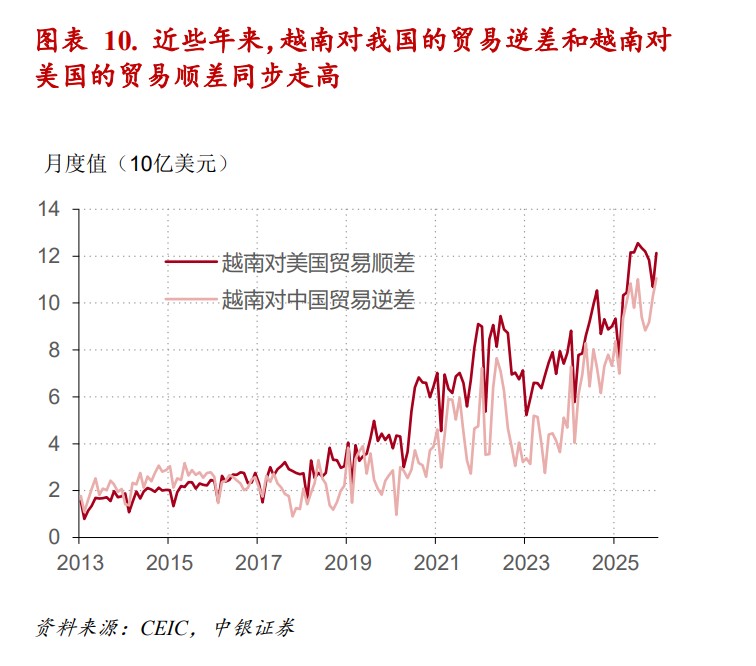

In recent years, the decrease in China's direct trade surplus with the U.S. is more due to China's transformation of direct trade surplus with the U.S. into indirect trade surplus through "re-exports" via third countries. For example, since 2020, Vietnam's trade deficit with China (China's trade surplus with Vietnam) and Vietnam's trade surplus with the U.S. have both risen simultaneously. After the U.S. implements the "reciprocal tariff" policy in April 2025, although China's exports to the U.S. plummet, total exports remain robust, supported by "re-exports." Thus, despite the significant decline in the proportion of the U.S. in China's trade surplus, the U.S. remains the primary source of China's external demand. The pull of the U.S. on China's external demand increasingly relies on the re-exports through third countries.

Since 2020, China's trade surplus has rapidly increased for two reasons. One reason is the disruption of production activities in countries around the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic from 2000 to 2022. China, having managed its pandemic response effectively, experienced less impact on production activities, leading to a significant increase in net exports. However, the impact of the pandemic has passed after 2022. A key reason for the continued significant rise in China's trade surplus is the weakening of the real estate sector since 2021, which has led to weak domestic demand. When domestic demand is insufficient, domestic production capacity tends to flow more towards overseas markets, resulting in a larger trade surplus.

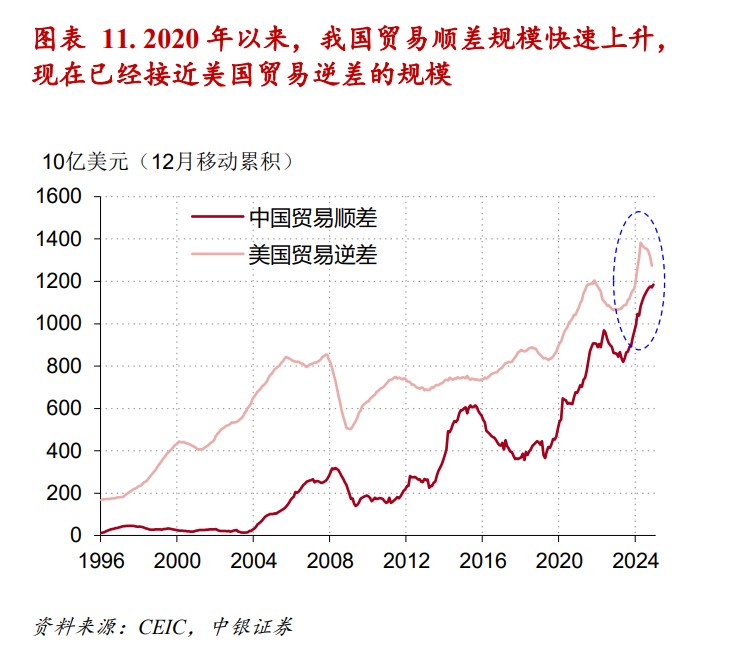

By 2025, China's trade surplus is expected to rise to $1.2 trillion, accounting for approximately 6% of that year's GDP, setting a historical high for China and creating a new record for the annual trade surplus of a single economy in human history. It is worth noting that Germany, as the world's third-largest economy in 2025, has a dollar-denominated GDP of about $5 trillion. This means that in 2025, China's trade surplus could account for about 1/4 of Germany's GDP that year More importantly, by 2025, China's trade surplus will be quite close to the trade deficit of the United States during the same period.

In the face of such a large trade surplus in China, we feel both joy and fear. The joy comes from the fact that it reflects China's unparalleled production capabilities, while the fear stems from the serious imbalance in domestic supply and demand it reveals, as well as the more severe external demand situation that China may face in the future. In the long run, the scale of the United States' trade deficit serves as a "ceiling" for China's trade surplus. If China's trade surplus exceeds this "ceiling," it will inevitably mean that other countries will experience trade deficits, putting them at risk of an international balance of payments crisis. To avoid such risks, these countries will inevitably adopt stronger protectionist measures to reduce imports and cut their trade deficits. Therefore, China's trade surplus cannot sustainably exceed the scale of the United States' trade deficit.

Risk Warning and Disclaimer

The market has risks, and investment requires caution. This article does not constitute personal investment advice and does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation, or needs of individual users. Users should consider whether any opinions, views, or conclusions in this article are suitable for their specific circumstances. Investment based on this is at one's own risk.